The Stories AI Tells Us/ Ourselves: Human-AI Mediation in the Workplace - and Its Implications

Roos Brekelmans

That Artificial Intelligence (abbreviated into AI) is one of technology’s current key topics of discussion – when looking at adoption and investment rates as well as lawsuits, legislation initiatives and broader tech trend reports – is no surprise. How advanced iterations of these technological capabilities will be adopted in the future will remain a guessing game, yet a plethora of anecdotal examples provide academic food for thought. Generative AI, a subset of AI, is currently one of the top tiers of interest within the field of AI, of which ChatGPT is one specific example: a Large Language Model (LLM) capable to answer questions and write texts as a conversational chatbot. These generative AI technologies are the focus of this paper.

Technological developments have historically impacted humans and how they perceive, experience and function within their world in relation to this technology, with Heidegger’s 1927 notion of Dasein (‘being-in-the-world’) as one of the first well-known concepts. In 1964 Marshall McLuhan wrote on explicit implications of modern technology, the “medium is the message”, on (2006). These words emphasise the fact that any medium transmits more than the knowledge is encoded through it. We do not merely use the medium, the medium uses us too. It follows that the medium defines – in one way or another – its message and in doing so, our perception of this message. This notion gave way to perspectives of phenomenology – the human experience – in relation to technology – such as Merleau-Ponty’s thoughts on embodiment. By looking at how we use media and how the media a/effect us, we can gain insight into how we approach and try to deal with reality. Whereas ‘traditional’ phenomenology could relate to specific physical instances of technology, with AI technology, its relationship and dynamic is much more disjointed and complex – thereby making a post-phenomenological lens appropriate.

As one of post-phenomenology’s great contemporary thinkers, Don Ihde emphasises the reciprocal relationship between humans and technology, focussing on how technological artifacts shape and mediate human perception and action (2012). The postphenomenological approach sees technology as transformative mediators of human-world relations rather than separated functional or instrumental objects or alienating entities (Verbeek in Hauser et al. 2018). Technologies mediate humans’ experiences and perceptions in and of the ‘world’. Applying this perspective to AI in the workplace, employees interact with intelligent systems that augment or automate various tasks, altering not only their roles, responsibilities, skill requirements – but also their experience. This dynamic reshapes the employees’ embodied engagement with work processes, as they adapt to new modes of collaboration, decision-making, and problem-solving facilitated by these AI technologies. The introduction of AI may even engender feelings of estrangement among employees as they navigate the evolving technological landscape and renegotiate their professional identities in relation to intelligent machines (Verbeek 2005). Technology itself becomes more and more invisible, transferrable (accessible through different physical devices or interfaces), pervasive, relational and performative. This applies to an even larger extend to current interactions of Generative AI.

This paper's goal is to position the technology of Generative AI within a broad theoretical framework of post-phenomenology, thus providing insights into the human experience in relation to AI technologies. Especially within the context of the workplace, acquiring knowledge on the e/affects of AI on the human experience is pivotal. Such insights can support organisations in making better and more intelligent decisions about adopting and using AI in relation to individual employee well-being and an overall healthy and sustainable workplace. It can inspire and support us in how to talk about and work with AI.

A Post-Phenomenological Exploration of AI

A post-phenomenological perspective on AI can provide key insights and better understanding for what impact AI as a tool has on employees and organisations engaging with these technologies. We will show how AI uniquely mediates human experiences, reshapes cognitive and emotional processes, raises ethical concerns, alters social dynamics, and is influenced by cultural contexts, necessitating a distinct lens when assessing its impact on employees and organisations.

So: what does approaching the topic of AI from a post-phenomenological perspective mean for organisations and employees engaging with these technologies? Their relationship with the world, its reality and the concept of truth – the stories they are using to mediate their work change. Not only does AI impact the existential level of technological mediation: how humans appear in their world, but also on a hermeneutic level: how the world appears to humans (Verbeek 2005). This doubled mediation seems to create a bigger Marxist Entfremdung (estrangement). Although Marx’ commentary on the estrangement between the worker and its labour-related output needs to be situated in his time, where he argued against factory work which created literal, physical estrangement between workers and their results, the same conceptual argument can be applied to employees working with AI-technologies.

Do the words on creation on “[h]ow could the worker come to face the product of his activity as a stranger, were it not that in the very act of production he was estranging himself from himself […]” not ring differently yet very true when situated in the era of ChatGPT used for papers or court arguments (Marx 1844)?

This notion of estrangement is familiar within the post-phenomenological perspective and illustrates a need for a multilayered view on technology in relation to humans.

Basic technological phenomenology states that ‘something’ always happens whenever we interact with any technology from an ontological perspective, so what makes AI so different (Ihde, 1990)? The way LLM’s such as ChatGPT present their output feels unique, often human and very truthful – but it is not (Weiser 2023). It is as if technology itself mediates its output towards us humans – and we need to mediate it back to our reality. The stories we tell, the stories we read, the stories we ingest, are coming more and more from from AI. Employees are already more inclined to ask an LLM for advice than their human colleagues – what does that mean for how we make sense of the world (Retkowsky et al. 2024)? Post-phenomenological perspectives on how technologies are understood are framed as human-technology relations that help constitute a world – a world that can be perceived as “leaking”, connecting our experiences situated in a real and perceived world (Zwier et al. 2015).

Summarising, approaching AI from a post-phenomenological perspective reveals the many and complex implications this technology has for both employees and organisations. Unlike traditional tools (e.g. electricity or computers) that enhance human capabilities, AI fundamentally alters the fabric of human experience, reshaping how we interact with knowledge, navigate relationships, and construct our understanding of reality. As employees will turn to AI for guidance more, they risk becoming estranged not only from their outputs but also from their own identities and roles within the organisation. This estrangement reflects a deeper ontological shift, where AI’s capacity to produce outputs that seem convincingly human fosters a deceptive sense of reliability, prompting individuals to mediate their realities through a lens heavily influenced by technology. The stories that employees tell and the narratives they engage with are increasingly shaped by AI, raising critical questions about authenticity, trust, and the nature of human agency. Ultimately, the post-phenomenological lens not only deepens our understanding of AI’s impact but also serves as a valuable framework for reassessing the evolving relationship between humans and technology in the workplace.

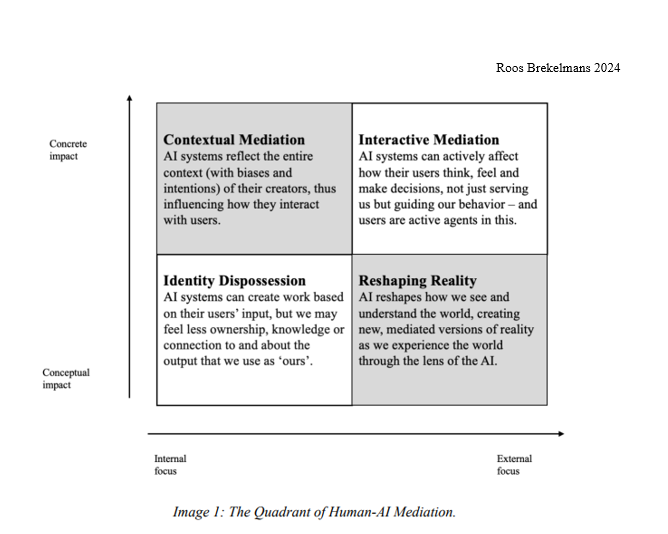

The Quadrant of Human-AI Mediation

Human-AI mediation is the complex process through which humans interact with AI and how AI reshapes human experiences. We distinguish four different types of human-AI mediation that are visually situated within one quadrant. The goal is to show how broad and especially diverse the impact of human-AI mediation is on/ for the human experience. And subsequently the (massive) potential consequence within any place place of work or education where this technology is being used.

Contextual Mediation

Philipp E. Agre, in 1997 said that “I tried to construct AI models that seemed true to my own experience of everyday life,” underscoring how AI systems inevitably reflect the experiences and biases of their human creators. This idea forms the basis of the first quadrant of human-AI mediation, which shows how AI systems are innately shaped by the socio-cultural, economic, and ethical contexts in which they are developed. Crawford (2021) argues that these systems carry the biases, intentions, and objectives of their creators, whether individuals, corporations, or institutions, and embed them into the very architecture of the AI. Consequently, AI users interact with tools that carry unseen yet significant biases, which mediate their perception and decision-making processes. The non-neutrality of LLMs becomes especially evident when we consider their training data, which is often drawn from extensive datasets influenced by specific worldviews, cultural norms, and entrenched historical biases. As Noble showed, AI systems, by their nature, mirror the social and power structures from which they are derived, replicating and even amplifying societal inequities (2018). LLMs, while seemingly impartial, reflect the inequalities, racialised discourses, and ideological perspectives embedded in their source material. This creates a mediated experience where users are interacting not with an unbiased system, but with a model that echoes the power dynamics and values of the society that created it. In this sense, AI not only mediates human interaction but actively contributes to the reproduction of existing social and cultural hierarchies. The act of creating an AI-model itself is therefore a first level of mediation between the human – and all of its contexts – and the technology.

Interactive Mediation

Secondly, whenever someone interacts with an AI, they subsequently project their own thoughts, intentions, emotions and subjective experiences onto the AI during their interactions with it. In this sense, LLMs serve as cognitive extensions, mirroring and amplifying the user’s ideas. This echoes Don Ihde’s concept of hermeneutic mediation, of how technologies mediate human understanding of the world. Users do not simply and passively receive information; they actively engage with the AI, thereby shaping the outcomes of the interaction and being an active part of the entire performance. Simultaneously, the output of a Generative AI will make us feel like it is correct and highly believable, mediating its own knowledge – whereas still very often the ChatGPT’s and other LLM’s of today hallucinate with some terrible consequences (Merken 2023). This type of human-AI mediation can also be linked to the notion of affective computing – as AI systems are more and more able to influence emotions of their users4 (Picard 2000). This perspective on human-AI mediation is particularly interesting because it aligns with the broader framework of human-technology mediation articulated by theorists such as Marshall McLuhan and Peter Paul Verbeek. McLuhan’s assertion that “the medium is the message” suggests that the characteristics of the technology itself shape human experiences and societal structures. Verbeek extends this idea, emphasising the ethical implications of technology’s role in shaping human behavior (2005, 2011). Collectively, these insights underscore the profound impact of human-AI interactions, highlighting the necessity of critically engaging with the implications of AI’s cognitive and emotional mediating roles, as they reshape our understanding of agency, knowledge, and reality. Through the inter-acting with an AI-model that replies to an initial human input – which is already mediated as it is prepared specifically for this model – and which delivers a response, to which a human reply can follow again; there is a second and more complex level of human-technology mediation.

Identity Dispossession

Thirdly, feelings of estrangement may occur when interacting with LLMs, especially when the AIgenerated outputs, although based on the user’s input, do not evoke a sense of ownership or personal accomplishment. Although depending on the context and purpose of the AI-query, the feeling of awe or pride that (sometimes) follows a challenging task endeavour is very likely to lack completely (Vredenburgh 2022). This broad sense of estrangement relates to Marxist alienation – where workers become detached from the products of their labor – as applied to intellectual or creative labor mediated by AI. Users often feel that while the output was generated based on their ideas, the AI’s contribution dilutes their personal investment, making the final product feel foreign or disjointed from their own creativity. Contemporary scholars like Zuboff highlight how AI systems, through the commodification of personal data, create a disconnect between individuals and their own digital identity, mirroring Marxist estrangement in a different sense (2019). Similarly, Floridi’s philosophy of information ethics shows how humans are increasingly estranged from their decision-making processes, as AI systems mediate, shape, and sometimes dictate choices previously left to human judgment (2014). This digital estrangement mirrors the Marxist critique of capitalism, where workers are alienated from their actions and its outcomes, with AI now alienating individuals from their sense of agency, privacy, and ethical engagement. Even in a broader and more personal sense, writing a poem by hand versus a poem written by an AI, will have very different feelings of ownership, pride and connectedness when presented to the object of the poem. This is just one, small, example but the potential impact on the human experience is clear to see. The third level of human-AI mediation is more distancing than that it feels mediating in a positive sense – as here the focus lies on the feelings the human user/ mediator has during and following the interaction with the AI. The identity of self, either as a creative poem-writer or a human at work, is being chipped away at when a lot of meaningful tasks can be fulfilled by an AI. This is a problematic space of human-AI mediation that will have significant impact on employee performance and well-being.

Reshaping Reality

So “[i]f chatbots are seen as a medium, their effects are not necessarily noticed in the direct relationships with them, but instead in the societal expectations arising from the availability of the technology, i.e., in the background” (Laaksoharju 2023).

This brief citation illustrates clearly how an AI far beyond its direct impact in interactions, can have a significant impact on the wider world it performs in. The stories we tell, the stories we read, the stories we ingest, are coming more and more from from AI. In this fourth corner of human-AI mediation, the effect extends beyond a personal dynamic and moves into the broader construction of reality, thereby fundamentally altering how its users perceive and interact with the world. LLMs produce outputs that shape not only individual tasks but also the broader frameworks through which users interpret their work and their social environment. AI outputs create a new, mediated version of reality – one that may diverge from unmediated human experience, leading to a sense of estrangement from the pre-AI world. This corresponds with Heidegger’s concern with technology as a world-revealing force, where AI systems reveal a world structured by their own logic and data, distancing users from an unmediated understanding of reality. In this quadrant, we see the effect of what Verbeek also called “leaking” into the world, shaping and changing broad societal expectations and perspectives (2005). This “leakage” into the real world meant that the mediation that occurs between humans and technology is not contained within a specific task or moment – it spills over, shaping broader social, cultural, and ecological realities. This kind of leakage has further significant impact as it shapes ethical and existential decisions and conditions in the real, physical world. The fourth domain of human-AI mediation is the most indirect, complex and simultaneously the most impactful. The consequences, experiences, opinions and perspectives we acquire, learn or perceive when interacting with an AI manage to simmer through into our real world actions. Thereby, the attitudes of AI will become physically present in our world – and although a world governed by humans does not always mean the best and most peaceful results, having a technology have such impact on our life world, may warrant more specific guard rails.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these four domains of human-AI mediation in the quadrant highlight the many ways in which AI influences our human experiences. It is a first attempt at creating a framework and structure to the multiple complex ways in which AI technologies will shape our human experiences. The quadrant of human-AI mediation attempts to follow Ihde’s postphenomenological and somewhat empirical approach to the human-technology relationship and describing and situating these effects and affects of/ on human experiences as concretely as possible. It may be clear by now that far from being neutral tools, AI systems significantly impact how individuals think, create, perceive and exist within the world. By explicitly acknowledging these varied levels of mediation, organisations can better understand and anticipate the broader social, ethical, psychological and organisational consequences of using AI technologies. Once more: why does this matter? Because of how this technology fundamentally changes the human experience, there is a concrete and significant impact within workplace context specifically: on (mental) wellbeing, knowledge and skill acquisition and perception. Further research on broader conceptual and philosophical considerations should include how a technology – in this case a specific AI artifact – is built on innate ‘technical’ perspectives versus critical philosophical and ‘weird’ human creative thinking. Additionally, human-AI mediation’s broader and more complex impact on social structures, collaboration, interpersonal experiences and power structures within the work place warrants further research. Finally, qualitative research on how human workers actually experience these types of AI technology in the work place would be a great continuation of this paper.

References

- Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

- Dempere J, Modugu K, Hesham A and Ramasamy LK (2023). “The impact of ChatGPT on higher education”. In: Front. Educ. 8:1206936. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1206936

- Edelman AI Center of Expertise (2019). “Edelman Artificial Intelligence Survey”. Edelman. https://www.edelman.com/research/2019-artificial-intelligence-survey Accessed: 13th of May 2024.

- Gabriel, I., Manzini, A., Keeling, G., Hendricks, L. A., Rieser, V., Iqbal, H., ... & Manyika, J. (2024). “The Ethics of Advanced AI Assistants.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.16244.

- Heidegger, M. (1977). The question concerning technology and other essays. (trans: Lovitt, W.). New York: Harper and Row.

- Heidegger, M. (2008). Being and Time. (trans: Macquarrie, J. & Robinson. E.). New York: Harper & Row.

- Hauser, Sabrina & Oogjes, Doenja & Wakkary, Ron & Verbeek, Peter-Paul. (2018). An Annotated Portfolio on Doing Postphenomenology Through Research Products. 459-471. 10.1145/3196709.3196745.

- Ihde, D. (1990). Technology and the lifeworld: From garden to earth. Indiana University Press.

- Ihde, D. (2010). Heidegger’s technologies: postphenomenological perspectives. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Ihde, D. (2012). “Postphenomenology and Technoscience: The Peking University Lectures.” Albany: SUNY Press.

- Laaksoharju, M., Lennerfors, T., Persson, A., Oestreicher L. (2023). “What is the problem to which AI chatbots are the solution? AI ethics through Don Ihde's embodiment, hermeneutic, alterity, and background relationships.” In: Ethics and Sustainability in Digital Cultures.

- Marx, Karl. (1959). Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Progress Publishers, Moscow.

- Mehr, Hila, Ash H, and Fellow, D. (2017). “Artificial Intelligence for Citizen Services and Government Ash Cent. Democr. Gov. Innov. Harvard Kennedy Sch . August 19, 1–12. Merken, Sarah. (2023). “ New York lawyers sanctioned for using fake ChatGPT cases in legal brief”. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/legal/new-york-lawyers-sanctioned-using-fake-chatgptcases-legal-brief-2023-06-22/

- McLuhan, Marshall. (2006). Understanding Media. New York: Routledge. McLuhan, M. & Fiore, Q. (2001). The medium is the massage: an inventory of effects. Gingko Press.

- Nader K, Toprac P, Scott S, Baker S. (2022). “Public understanding of artificial intelligence through entertainment media”. In: AI Soc. doi: 10.1007/s00146-022-01427-w.

- Neumann, O., Guirguis, K., & Steiner, R. (2024). “Exploring artificial intelligence adoption in public organizations: a comparative case study”. Public Management Review, 26(1), 114-141.

- Noble, Safiya Umoja. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press. Patel, Vinay. (2024).

- “AI Girlfriend Tells User 'Russia Not Wrong For Invading Ukraine' and 'She'd Do Anything For Putin’”. In: International Business Times. Accessed 14th of May 2024. https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/ai-girlfriend-tells-user-russia-not-wrong-invading-ukraine-shed-doanything-putin-1724371

- Retkowsky, J., Hafermalz, E., & Huysman, M. (2024). Managing a ChatGPT-empowered workforce: Understanding its affordances and side effects. Business Horizons.

- “Stanford AI Investment Index Report 2024”. (2024) https://aiindex.stanford.edu/report/ Accessed: 13th of May 2024.

- Sundar, S. Shyam. (2020) “Rise of machine agency: A framework for studying the psychology of human–AI interaction (HAII)”. In: Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 25.1. 74-88.

- Tiernan P, Costello E, Donlon E, Parysz M, Scriney M. (2023) “Information and Media Literacy in the Age of AI: Options for the Future”. In: Education Sciences. 13(9):906. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090906

- Verbeek, Peter-Paul. (2005). What Things Do: Philosophical Reflections on Technology, Agency, and Design. 10.1515/9780271033228.

- Verbeek, P-P. (2011). Moralizing Technology: understanding and designing the morality of things. University of Chicago Press.

- Vredenburgh, Kate. “Freedom at Work: Understanding, Alienation, and the AI-Driven Workplace.” Canadian Journal of Philosophy, vol. 52, no. 1, 2022, pp. 78-92.

- Zhou, M., Abhishek, V., Derdenger, T., Kim, J., & Srinivasan, K. (2024). “Bias in generative AI”. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.02726.

- Zwier, J., Blok, V. & Lemmens, P. (2016). “Phenomenology and the Empirical Turn: a Phenomenological Analysis of Postphenomenology”. In: Philos. Technol. 29, 313–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-016-0221-

© Copyright Roos Brekelmans 2024.

We hebben je toestemming nodig om de vertalingen te laden

Om de inhoud van de website te vertalen gebruiken we een externe dienstverlener, die mogelijk gegevens over je activiteiten verzamelt. Lees het privacybeleid van de dienst en accepteer dit, om de vertalingen te bekijken.